Innovation in the First Fintech Cycle

A framework for thinking about uncertainty, risk, valuations, upside, “smart money,” and incumbent positioning, built through an analysis of the First Fintech Cycle, circa 2007-2023.

A recent essay by Nicolas Colin prompted us to reflect on the topic of risk in venture. The resulting framework ended up being a useful lens for evaluating what we call the First Fintech Cycle, circa 2007-2023.

Theory: Risk vs. Uncertainty and the impact on returns

As Colin points out, much great work has been done on risk in early-stage venture, including by economist Frank Knight and Jerry Neumann.

A few key points stood out to us after reviewing the literature:

- There are two categories of risks in new ventures: quantifiable and unquantifiable. Knight refers to the former as Risk and the latter as Uncertainty (we’ll use the same terminology throughout this piece).

- Examples of Risk (quantifiable) include: Can we deliver the plan on time and on budget? Can we hire and manage high quality employees, suppliers and partners to deliver our product/service? Can we contact and convince the right known buyers? Can we obtain necessary licenses/approvals/patents?

- Examples of Uncertainty (unquantifiable) include: Is this technically possible? Will anyone want this if it works? Can we secure continued access to funding while we scale up? If it works, and people want it, does a sustainable business model exist to deliver it? Is it possible to outcompete incumbents in this space?

- The most potentially valuable new ventures are the ones that operate in areas of significant Uncertainty, where there is no precedent for their work or data to support demand. Paul Graham of Y Combinator has written about this idea. This type of innovation is difficult for incumbents to fund because ROI cannot be meaningfully calculated.

- In domains with high Uncertainty, the likelihood of failure is increased, but outcomes are uncapped and potentially enormous, as successful companies are defining brand new markets.

- In domains with higher Risk (relative to Uncertainty), by contrast, incumbents/corporates likely have the advantage due to existing processes, access to resources, and economies of scale. In such domains, economic upside is more predictable but more limited.

- Importantly, Risk is only quantifiable within sufficiently well-known and well-defined domains, with observable precedents and historical data.

A lens for analyzing fintech

How does the theory manifest in practice in the fintech industry?

Colin makes the interesting point that B2B SaaS companies now have a well-defined playbook, meaning Uncertainty is now sufficiently low. Whereas once building B2B SaaS was characterized by high Uncertainty, now the primary risks are quantifiable. If that’s the case, the theory suggests, potential outcomes for new companies in the space should be capped.

Depending on the size of the market, capped can still be large, but the next B2B SaaS startup following the industry-standard playbook is less likely to achieve an exponential outcome.

The difference between Risk and Uncertainty in Knight’s definition is subtle in practice, especially in software businesses, but it’s a useful concept in thinking about risk/return tradeoffs for new ventures.

Far from just B2B SaaS, between the beginning of the most recent fintech cycle circa 2007 (with the founding of Mint.com) and today, the entire industry has generally evolved from operating in a place of high Uncertainty, moderate Risk and uncapped upside to one of relatively lower Uncertainty, moderate Risk and capped upside. As this transition played out, the risk/return profile of the average fintech changed accordingly.

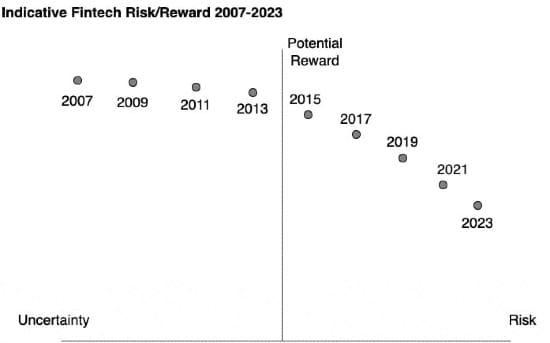

If the theory holds true, the trajectory over time might look something like this:

Uncertainty over the cycle

In the early days of fintech, much of the entrepreneurial energy came from the rejection of the financial incumbency in response to the Global Financial Crisis, and the opportunity came from bringing basic digitization via mobile, cloud and eventually APIs to bear on consumer and B2B financial services.

The financial crisis also created space for fintechs to compete as incumbents pulled back from certain markets, especially consumer and SMB lending, as a result of increased risk aversion and capital requirements.

Uncertainty was high at the beginning of the cycle, with important questions still unanswered, including:

- Is this technically possible?

- Will anyone want this if it works?

- If it does work and people want it, can we build a sustainable business model around this?

- Is it possible to disrupt/outcompete incumbents?

Over the course of the cycle, consumer demand for digital financial services matured, affirmatively answering the question “will anyone buy this?” Technological and regulatory partnership models were developed allowing fintech startups to offer regulated products in conjunction with banks, answering the question “is this product/service technically feasible?”

At the same time, the question “does a sustainable business model exist to deliver this product/service?” was never affirmatively answered in many areas of fintech, leading to much capital loss.

As to the question “is it possible to outcompete incumbents?,” it is more nuanced. It only matters whether it’s possible to outcompete incumbents where a sustainable business model exists. Outcomes from the cycle tell us that the better question is actually “is it possible to create a product/service with a sustainable business model that is sufficiently adjacent to incumbents to avoid competing with them?” That is to say, the most successful fintechs in the first cycle grew in greenfield or adjacent markets rather than displacing incumbents head-to-head.

Mapping the cycle

The First Fintech Cycle covers the period from 2007-2023, initiated by the founding of Mint.com and (hopefully) ending in 2023 with the deep freeze that is currently paralyzing early- and growth-stage fintech.

The cycle can be broadly mapped as follows, through the lens of Risk/Uncertainty theory:

Early fintech (circa 2007)

Technical feasibility, customer demand, access to funding, regulatory response, and competition from incumbents were all big open questions facing early fintechs, but the market share and revenue pool available to successful companies were potentially enormous.

Examples of companies founded at this time include Mint.com, SoFi, Betterment, Simple, Stripe, Square.

Many business strategies during this phase focused on B2C and broad-based disruption of incumbents.

Circa 2015

By the middle of the innovation cycle, the Risk/Uncertainty balance had evolved. By this point, Uncertainty was falling.

Technical feasibility was no longer a question. Cloud was freely accessible, robust enough for financial services use cases and broadly accepted by regulators. Access to infrastructure including payments systems, card issuing and processing, brokerage, and clearing and settlement was increasingly digital, API-based and available to startups.

Customer demand for digital financial services from startups was proven if not mainstream.

While some key questions had been answered, Uncertainty was still relatively high. The incumbent response was unknown, and sustainable business models had not been established in much of fintech.

Examples of companies founded during this golden age include Robinhood, Monzo, Revolut, Nubank, OakNorth, Allica, Coinbase, Brex, Plaid, Chime, Circle.

Business strategies during this phase varied widely, targeting new and existing markets and all customer types.

Circa 2023

Today, most of the big open questions that created Uncertainty in 2007 have been answered in the context of this specific innovation cycle.

- Yes, it is technically feasible to build digital financial services.

- There is customer demand for certain fintech products and services if they create disproportionate value with high reliability and low risk.

- It is easier to realize outsized value for customers by creating a brand new market than by improving on currently available offerings.

- Yes, a limited number of fintechs can capture sufficient market share from incumbents to sustain (if not dominate). However, it is significantly easier to build a category leader in a greenfield space than in an existing market (radical innovation was higher earlier in the cycle, more on this later). It is also possible to build small/medium-sized, profitable businesses in existing market segments without delivering venture scale returns (incremental innovation, again, more on this later).

- Through the middle and end of the cycle, there was sufficient funding available to support successful ventures. This may or may not be the case in the future in different macroeconomic conditions and under different prevailing investor preferences.

- Specifically, there was a tremendous influx of risk-seeking capital as the cycle progressed, driven by persistent low interest rates and COVID-related stimulus. This additional capital increased valuations at all stages but did not appear to meaningfully influence the Risk/Uncertainty trajectory over the cycle or the likelihood of exponential outcomes.

Examples of companies founded late in the cycle include: Pipe, Deel, Ramp, Pinwheel.

Many business strategies during the later stage of the cycle focused on serving startups and scale-ups, especially by providing risk, compliance and operational tooling or lending.

Note: I’ve intentionally left out crypto/web3 companies to better track the fintech cycle. There’s a great opportunity to replicate this analysis with a focus on that space.

A closer look

As discussed, as the cycle progressed, the market evolved, and the characteristics of new businesses changed accordingly.

How did the relationship between Uncertainty and Risk evolve from 2007 to 2023, especially with respect to innovation, investment and outcomes?

The difficulty in quantifying Uncertainty and Risk make strict analysis difficult, but anecdotally we can observe a few important dynamics.

Uncertainty/Risk vs. Funding

New ventures operating in areas of high Uncertainty have by definition more potential than others to be innovative. The mere presence of high Uncertainty means an area has not previously been sufficiently explored.

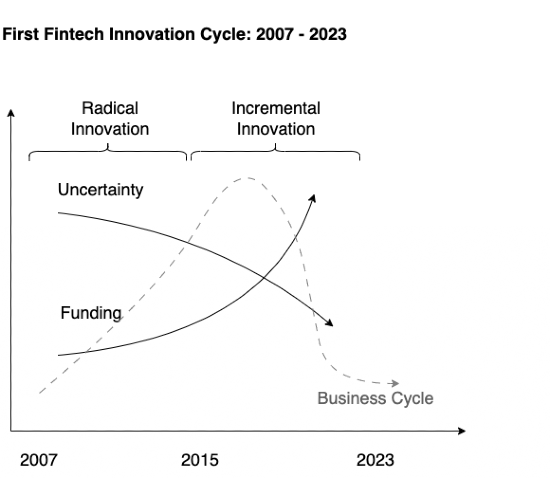

Naturally, there is more greenfield space at the beginning of an innovation cycle. We indeed observed more attempts at radical innovation in the first half of the fintech cycle, when Uncertainty was high. As the market became more saturated with new ventures, resulting in less available greenfield space, and Uncertainty fell, the industry’s focus shifted to more incremental innovation (see chart below), as confirmed anecdotally in Mapping the Cycle, above. (Note: Risk/Uncertainty change over time for the same business as it makes progress. Different investor types are relevant for different rounds because of this changing risk composition.)

Counterintuitively, this apparent reduction in radical innovation (ex-crypto) occurred even as increasing amounts of venture capital were entering the market.

As the cycle progressed, the amount of funding for fintech increased tremendously, even adjusting for global VC growth (a proxy for risk-seeking capital availabile in the economy).

![[] https://www.svb.com/trends-insights/reports/fintech-industry-report/2021/ (RIP)](https://www.rebank.cc/content/images/2023/12/DraggedImage.png)

Charting the 2007-2023 cycle, we see something like this:

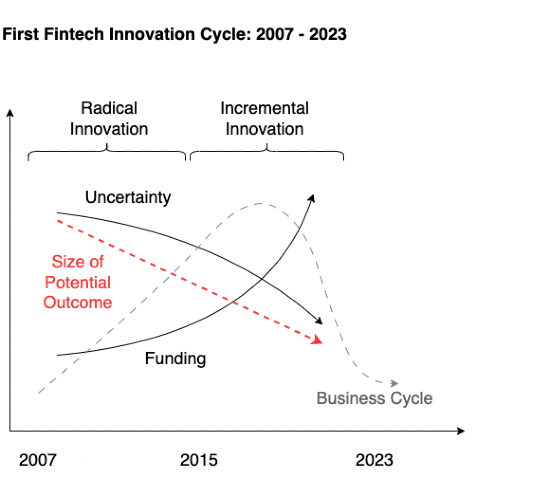

As Uncertainty fell, the theory suggests, the potential size of successful outcomes should have fallen as well, adjusted for available capital in the ecosystem. If the theory is correct, the chart might look something like this:

In such a dynamic market as fintech, it is difficult to isolate the size of outcomes with respect to Uncertainty vs. Risk, but the idea is worth reflecting on, especially for founders and investors.

Over the course of the cycle, even with more risk capital theoretically available to fund moonshots, did the industry focus increasingly on areas with less Uncertainty, with a resulting reduction in outcome potential? Anecdotally, we believe it did.

Undoubtedly, Uncertainty in fintech naturally fell as we started getting answers to the most important questions that can be formulated around mobile/cloud/APIs + prevailing customer behavior + existing market structure. However, other factors potentially contributed to this reduction in Uncertainty as well and the corresponding shift to incremental innovation. We point to two primary factors: maturing founder profiles as the cycle progressed, with more former operators bringing pre-validated venture ideas informed by existing industry pain points, and investor preferences. While the potential impact of founder profiles is difficult to fully unpack, we’ll explore investor preferences in more detail.

Investor composition

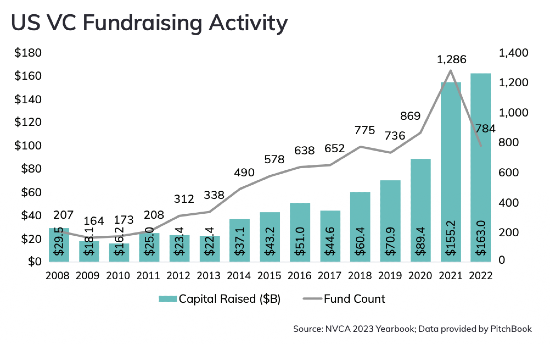

Over the course of the cycle, there was an influx of new venture investors. For example, in the US, annual VC fundraisings increased from around 200 in 2008 to over 1,200 in 2021.

At the same time, the percentage of VC invested in fintech grew from 6% in 2012 to 18% in 2021, per the SVB chart presented previously.

Taken together, new venture firms and available funding supporting fintech exploded in the US over the cycle, and the same was true in key international regions as well.

Ben Horowitz and others have noted the counterintuitive nature of good startup ideas, many of which sound like bad ideas at first.

“A breakthrough idea looks like a stupid idea. If everybody recognized the idea as a breakthrough idea, it wouldn't be a breakthrough at all." - Ben Horowitz

Should we believe that the influx of new-to-venture investors had the experience and conviction to succeed in the hard task of backing billion-dollar ideas that sound objectively bad? If not, how are such investors likely to judge deals?

One way they could analyze investments is the same way they do in other areas of finance: traditional investment analysis, using techniques like market sizing, business plan evaluation, modeling and competitor analysis.

While highly relevant in calculating ROI and expected returns, these tools are less likely to predict exponential success in greenfield markets, where the majority of early-stage returns are generated, as previously noted by Paul Graham. To the contrary, traditional investment analysis methods are more likely to favor lower Uncertainty businesses, where sufficiently reliable data is available to inform modeling.

In practice, it is not difficult to see how new-to-venture investors entrusted with LP money could have sought the “safety” of traditional investment decision-making to justify their actions, favoring quantifiable (lower Uncertainty) ventures as a consequence and thereby reinforcing the market evolution toward incremental innovation.

Incumbents

The changing risk dynamics inherent in business strategies over the cycle had important implications for investors, founders and incumbents.

Incumbents, especially publicly traded companies, tend to favor investments with quantifiable ROI, supporting capital allocation decisions as well as reporting and guidance to shareholders. Similarly, incumbents are generally hesitant to divert resources from a profitable core business to potentially competitive innovation initiatives until strictly necessary (and sometimes not even then).

With these preferences in mind, we can see why incumbents were slow to pursue innovation early in the cycle, when Uncertainty was high. However, as the cycle progressed, incumbents started experimenting with and replicating fintech innovations, especially as customer demand for digital financial services grew. At scale, these experiments had mixed results, highlighted by notably poor outcomes like JPMorgan’s Finn and Goldman’s Marcus businesses, whereas some leading incumbents in the UK, Singapore, Turkey and a few US regionals did a great job of building digital competency, improving front and back office capabilities and unlocking access to the fintech ecosystem. Incumbent activity in fintech will potentially culminate in a consolidation process that could play out over the next 12-18 months, through the beginning of the next cycle.

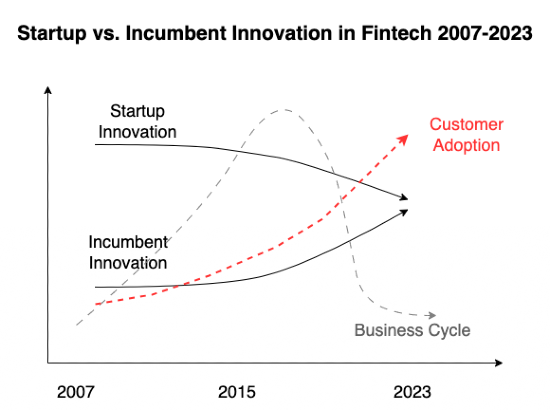

In summary, while fintech innovation was falling over the cycle from an early peak, incumbent innovation increased from a low base as opportunities were validated, quantified and eventually incorporated into existing organizations.

We can visualize startup vs. incumbent innovation over the cycle like this:

Today, at the end of the cycle and in an environment of reduced venture activity, incumbents across banking, investments and insurance are playing an important role in driving fintech.

Over the next 12-18 months, look for global incumbents to make investments based on learnings from the cycle and the availability of cheap assets, while setting the tone for ROI and profitability discipline, key elements required to consolidate innovation gains from this cycle into the fabric of the industry. Both of these incumbent activities play a vital role in clearing the early-stage venture market and resetting it for the next innovation cycle.

This phase of relative equilibrium, with venture activity muted and well-positioned incumbents and fintech winners consolidating gains, will persist until the next cycle begins in earnest.

The next innovation cycle

What will the next fintech innovation cycle look like?

As the saying goes, “history doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes.”

To inform our expectations, let’s review what we observed in the last cycle:

- New technological breakthroughs created new tools for entrepreneurs and innovators to bring to bear on a static industry.

- Strong emotional rejection of the traditional industry energized founders and early-adopter customers.

- A relatively small number of venture capital firms funded early visions of radical disruption with exponential potential outcomes.

- Existential questions about the feasibility and viability of new innovations were answered by early companies.

- More founders and capital flowed to the industry as Uncertainty fell.

- New ventures with widely varied strategies proliferated, driving up competition among startups.

- Low interest rates that started at the beginning of the cycle persisted, resulting in high availability of risk-seeking capital and an increase in new venture investors.

- Founders and investors increasingly focused on lower relative Uncertainty strategies, driven by a variety of factors, resulting in a lower likelihood of exponential outcomes.

- Incumbents increasingly entered the market as Uncertainty fell and customer behavior adapted to earlier innovations.

- A glut of VC capital and competition to deploy it led to looser investment criteria and diligence.

- A sudden pullback in capital availability and spike in the cost of money (due to macroeconomic stress resulting in sharply higher interest rates) led to a collapse in venture valuations and unavailability of additional funding to the majority of fintechs.

- Unprofitable companies dependent on new investment capital risk failure, while profitable or cash-rich companies cut costs and slow growth dramatically to wait out the bear market. The very few best positioned ventures and incumbents consolidate competitive advantages and market share during the downturn. (We’re here at the time of writing)

- Most likely, a period of consolidation will accompany the market recovery, with failed ventures being acquired or liquidated as capital and risk appetite return to the market.

- At some point, new technological breakthroughs and/or customer behavior changes will start a new cycle.

While it’s too early to make predictions about the next cycle, AI is the obvious potential catalyst to drive it.

Lessons

If the trajectory of the First Fintech Cycle as outlined above is a template for what the next cycle may look like, a few important reflections stand out.

Greenfield markets represent the best opportunity to build great businesses. Competing with incumbents in existing market segments, even with new technology, is less likely to produce large businesses with strong economics and a defensible moat. There are more greenfield opportunities at the beginning of the cycle than there are at the end.

Founders and investors should think about whether they’re operating in areas of greater or lesser Uncertainty and by extension pursuing radical or incremental innovation. Higher Uncertainty, radical innovation can result in exponential outcomes, with a high risk of failure if reality does not prove to align with hypotheses. Lower Uncertainty, incremental innovation is more likely to result in capped upside. However, if strategy and execution are good, success can be more predictable in lower Uncertainty businesses, with the crucial caveat that competition can be high. In competitive markets, margins and returns may be lower, which should inform capital allocation and valuations. Mistaking one category of venture for the other can result in over- or underfunding, venture and product mis-pricing and over- or underpayment for customers.

In this cycle, companies failed to transition from growth to profitability while the resources were available. Uber’s “blitzscaling” strategy of raising and spending huge amounts of money to subsidize user growth with negative unit economics, an approach championed by LinkedIn founder and investor Reid Hoffman, informed many misguided strategies in fintech. As a result of a general failure to focus on sustainable economics rather than growth, successful outcomes during the cycle were few relative to the number of ventures and investment. Growth metrics drove high valuations at the peak of the cycle, but the failure to translate users and investment capital into profitability ultimately led to massive value destruction when capital availability disappeared.

What’s next?

How will the next cycle be similar to or different from the last one? Will it create more sustainable value?

It’s difficult to say.

Why? Because, as the mathematician John Allen Paulos said, “Uncertainty is the only certainty there is.”